Petra Epperlein and Michael Tucker aka pepper&bones are filmmakers currently based in New York and Berlin. Children of the Cold War—Epperlein was born in East Germany and Tucker in Hawaii—their body of work is centered on armed conflict, human rights and extremism. They’ve directed more than a dozen feature films since 2004, including GUNNER PALACE, one of the first independent documentaries about the Iraq War, and most recently, THE MEANING OF HITLER. Their films have screened at festivals from Telluride to Toronto to the New York Film Festival, Edinburgh, Sarajevo, Amsterdam, Hong Kong, Berlin, Melbourne, Copenhagen and many more and are distributed in theaters, across streaming platforms and premium TV worldwide. They are currently filming in Ukraine.

*

The Army We Had

2023, The New York Times

Nearly 20 years after their deployment to Iraq was captured in “Gunner Palace”, veterans grapple with their younger onscreen selves to make sense of a war that has yet to be fully reckoned with. .

*

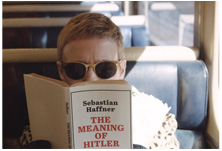

The Meaning of Hitler

2020, DOC NYC

Sheri Linden, The Hollywood Reporter

An intellectual inquiry with burning present-day resonance, The Meaning of Hitler is also a road trip through some of the darkest chapters of European history. In one of the artfully constructed film’s visual motifs, we watch the road itself through a windshield, a not-to-be-ignored Mercedes-Benz hood ornament positioned prominently in the frame. In this context it’s no status symbol, not when the route leads to such places as the Führer’s bunker and the Sobibór death camp.

The complicity of Daimler-Benz and countless other German companies in the Nazi war effort is not the subject of the film, but it is one of the many subtexts coursing through its rich synthesis of history and psychology. Through an exceptional collection of interview subjects, Petra Epperlein and Michael Tucker’s dynamic documentary examines the ways we think about the Holocaust — and the ways we choose not to. As one of those interviewees, novelist Martin Amis, observes, “Our understanding of Hitler is central to our self-understanding. It’s a reckoning you have to make if you’re a serious person.”

*

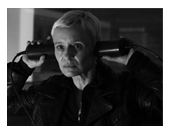

Karl Marx City

2016, TIFF and NYFF

Karl Marx City Revisits the Everyday Terror of Dictatorship

A.O. Scott, The New York Times

“Karl Marx City,” Michael Tucker and Petra Epperlein’s unsettling new documentary, is a smart, highly personal addition to the growing syllabus of distressingly relevant cautionary political tales. The volumes currently crowding bookstore front tables — George Orwell’s “1984,” Sinclair Lewis’s “It Can’t Happen Here,” Hannah Arendt’s “The Origins of Totalitarianism” — offer time-tested prophecies and autopsies of dictatorship. “Karl Marx City” supplements their theories and speculations with everyday facts about life in the supposed workers’ paradise of the German Democratic Republic.

In 1999, 10 years after the collapse of East German communism, Ms. Epperlein’s father committed suicide. Fifteen years after that, his only daughter forces herself to confront the awful possibility that he might have collaborated with the Stasi. So many people did.

The mystery of her father’s life and death provides “Karl Marx City” with suspense, and with a concrete sense of profound moral and emotional stakes. Repressive regimes excel at creating ambiguity, at making complicity easier than resistance and at blurring the lines between heroes and villains. Ms. Epperlein and Mr. Tucker, shooting in black and white and making judicious use of historical footage, brilliantly evoke a landscape of gray areas. They also uncover glimmers of decency, loyalty and solidarity — the tiny cracks in the totalitarian edifice that foretold its eventual and inevitable collapse.

*

The Flag

2013, CNN FILMS

In a Puzzle, a Clearer Look at 9/11

Neil Genzlinger, The New York Times

“The Flag” does more than simply retell the familiar story or push the obvious buttons.The CNN film, based on a book by David Friend, focuses on the smudged American flag that three firefighters raised through the dust of the collapsed buildings at ground zero late in the afternoon of Sept. 11, 2001. A photograph of the flag raising taken by Thomas E. Franklin of the New Jersey newspaper The Record became a heartening, patriotic symbol for many on an otherwise awful day, and so did the flag itself. It flew at Yankee Stadium and on battleships in the Middle East — or so everyone thought. Somewhere along the line, the flag had disappeared, and an impostor had taken its place.

Trying to unravel the mystery is at the core of “The Flag,” but if the film had settled for that, it might have seemed to be trivializing a tragedy. The filmmakers, though, use this search as a way to examine the need people — especially politicians — had to create narratives and symbols after the attacks. And they remind us that the emotions surrounding Sept. 11 were more complex than they are often made to seem in lesser documentaries.

*

Fightville

2011, SXSW and IDFA

Fightville looks at cage fighting as a means to identity and an unending sales pitch, and also at the products sold, that is, vulnerable young men. Here the fighters are perpetually constructing their ideal selves, their bodies (and black eyes and broken noses and scars) emblems of their efforts. Dustin Poirier says he’s “full of joy” when he’s at work in the cage (though he also demurs from calling himself a professional fighter until he’s actually making a living at it; until then, he tells people, “I drive a delivery truck, I can’t lie to somebody”). As much as Dustin means to move on, to sign a contract with a company like the UFC, Albert Stainback concedes the show, practicing his stare in the mirror, donning a derby and white coveralls (after Alex in A Clockwork Orange) en route to the ring, posing as someone else to insist on his own creation.

So self-possessed, so aware of the performance, they nonetheless keep turning that performance around, rolling it on top of itself. “I want it to be my only option because I love it that much,” says Albert. “Maybe that’s a little foolhardy, but I don’t care.” Yet he does care. The film ensures you know that, as he appears again and again against the dark red wall of the locker room, exhausted while and because he pushes himself. Fighting is a fiction, but that doesn’t make it less true.

*

How to Fold a Flag

2009, TIFF

Scott Macaulay, Filmmaker Magazine

With their latest film, How to Fold a Flag, documentary filmmakers Michael Tucker and Petra Epperlein have come full circle. Their first feature was 2004’s Gunner Palace, which told the story of soldiers in the Army’s 2/3 Field Artillery as they patroled the streets of Baghdad in late 2003 and early 2004. Told in a gritty style that threw viewers right into the midst of conflict, the film resisted an overt political agenda, focusing instead on the daily lives of the troops.

Now, Tucker and Epperlein premiere at Toronto what they say is the final film in their series. How to Fold a Flag makes the natural journey from the Mid East to the States as it follow four soldiers, all featured in Gunner Palace, as they adjust to so-called normal life Any written summary of How to Fold a Flag must necessarily focus on these characters, four men who served in the same unit but whose various socio-economic and racial divisions separate them when they return home to America. But what starts off seeming like a traditional “vets returning home” documentary subtly morphs into a nuanced portrait of a country trying its best to emotionally distance itself from the reality of its foreign policy. Filmed in the months leading up to the election, the psychic temperature of this movie is far from the “Yes, we can!” moxie of those days. Indeed, Tucker’s keen-eyed cinematography captures an anxious America, one wrapped in the language of patriotism but unsure of its future. How to Fold a Flag is a moving film that has as much to say about America’s future as it does its recent past.

*

The Prisoner

or How I Planned to Kill Tony Blair

2006, TIFF and IDFA

An Iraqi Kafka

Richard Schickel , Time Magazine

Yes, you read that jokey-sounding title correctly. That font of wisdom, American “intel,” somehow gains the impression that the British prime minister, about to make an uplifting visit to the war zone, has been targeted for assassination. Therefore, a squad of American soldiers, acting on a bad tip, goes barging into the home of one Yunis Khatayer Abbas, looking for bombs, or bomb-making equipment, or anything that may incriminate him and his family in this dirty deed. All they find is a locked ammunition box that proves to contain shampoo and party decorations. What Abbas and his brothers — one of them a university student, another a doctor — get is a mess of trouble, a year of incarceration and sometimes brutal interrogation before they are set free.

The Prisoner is a wee little movie, only 72 minutes long, and it is very minimalist in approach — three interviews, a little action footage shot by Yunis and Tucker, with comic book cartoons (by co-director Epperlein) filling in the visual gaps in the story (a much more honest approach than using impersonal stock footage and a lot of pompous narration). But this punctiliousness, this refusal to inflate, grants it a large measure of persuasive power. You believe it precisely because it makes no claims it cannot document and, more important, because you imagine yourself in his sandals, trying desperately to prove your innocence to people who have no interest in that topic.

*

GUNNER PALACE

2004, Telluride and TIFF

With Soldiers in a Palace and Death in the Streets

A.O. Scott, The New York Times

“Gunner Palace” owes as much of a debt to small-screen vrit as it does to the loftier traditions of nonfiction cinema. It’s hard not to see jerky, breathless hand-held images of armed men in uniform cruising through rough neighborhoods without thinking of “Cops,” or to witness young Americans hanging out in their shared quarters, accoutered with headphones, laptops and other high-tech accessories, without being reminded of “The Real World.” Perhaps inadvertently, Mr. Tucker and Ms. Epperlein have glimpsed Iraq through the lens of American popular culture, and their film is also a mirror, reflecting back into that culture an image of itself at once utterly alien and entirely familiar. Mr. Tucker’s occasional voice-over narration is deliberately flat and prosaic. The rough poetry that his video camera captured belongs to the setting — a landscape that is bright, teeming and tense by day, eerie and murky by night — and to the soldiers, several of whom are talented free-style rappers and spoken-word declaimers. Their rhymes and beats punctuate the film and provide it with a dense, dizzying eloquence.

The raw inconclusiveness of “Gunner Palace” is the truest measure of its authenticity as an artifact of our time and of its value for future attempts to understand what the United States is doing in Iraq. Over the last few years, we have been subjected to an awful lot of certainty — from proponents of the war, from its critics and even from vacillators and equivocators. “Gunner Palace,” in its savage, intelligent, boisterous messiness, is a welcome antidote to the self-convinced rhetoric of pundits and politicians. Each time I have seen it, I have emerged feeling moved, angry, scared, hopeful, frustrated and dispirited — and grateful for this confusion, which is its own form of understanding.

*

©pepper&bones 2024